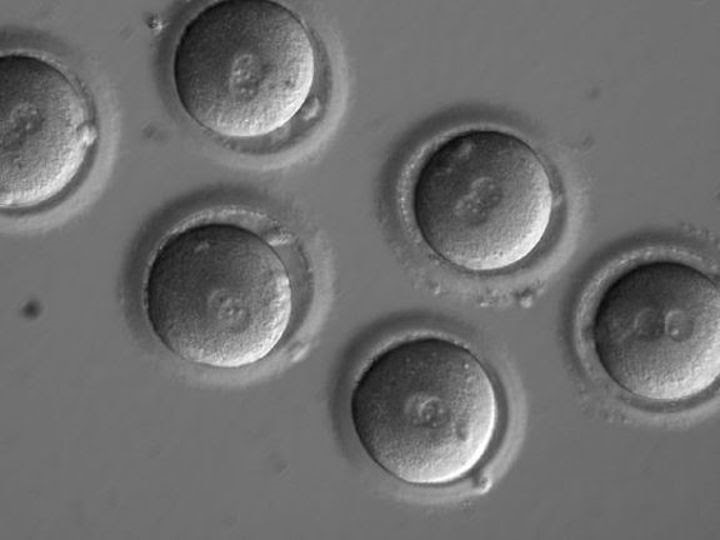

Scientists, for the first time, have used gene editing to correct a disease-causing mutation in viable human embryos, which could be a step toward genetically modified babies. The embryos in the study were destroyed and never intended to be implanted in a woman (illegal in the USA).

But the experiment takes the idea of editing genes before birth “from future fantasy to the world of possibility.” While the technique is not perfected, it is considered to be a big step forward, in spite of remaining safety and ethical questions. “We still have room to improve,” said Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a researcher at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland and lead author of the paper.

Mitalipov and his colleagues, including scientists in the United States, South Korea and China, recruited several healthy egg donors and one sperm donor who carried a gene for a common heart condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The disease can cause heart failure and sudden death in unsuspecting adults. Under normal conditions, half of the man’s children would inherit the gene, the disease and the risk for passing it on. They fertilized the eggs with the man’s sperm. At the same time, the eggs were injected with gene editing tools, called CRISPR, which included an enzyme primed to target and snip out the bad gene. The hope was the embryos would then repair the cuts with healthy versions.

They found that 42 out of the 58 embryos (72.4%) were free of the disease-causing gene, a clear improvement over the expected 50%. Also, the repaired embryos appeared free of unintended changes, such as misplaced gene cuts or a mish-mash of healthy and unhealthy versions of the target gene. Such worrisome changes were found in earlier, smaller Chinese experiments.

And they found one surprise: the embryos repaired themselves with DNA from the healthy egg, not a synthetic snippet provided by the researchers. That could limit the use of the method for introducing any sort of “designer” gene.

The technique would need to approach 100% effectiveness to be ready for clinical trials aimed at producing pregnancies, Mitalipov said. But, he said, the ultimate goal would be eliminating inherited risks for everything from cystic fibrosis to breast cancer. Prospective parents can already look for and eliminate known disease genes by going through in vitro fertilization and having the resulting embryos screened for the genes. One advantage of gene editing is that it might reduce the number of IVF cycles a couple would need to get healthy, unaffected embryos, said study co-author Paula Amato, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at OHSU.

Many scientists think embryonic gene editing should move forward “only for compelling reasons and under strict oversight.” But that would be hard to achieve. “There are still a lot of safety issues, a lot of legal and ethical issues,” even in medical uses, said Michael Werner, executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine in Washington, D.C. The group promotes the use of gene therapy to treat diseases, but has drawn a line at treating embryos.

“You are talking about permanently changing the genome of a person without their consent,” Werner said. “That’s an ethical question even if the technical challenges and safety get worked out.”

The antediluvian’s worked with genes for their own purposes, no doubt, from “good motives” at first. But they became very adept at creating all manner of chimeras, beasts and other amalgamations, that God saw that their purpose was “only evil continually.”

It was not multitudes or majorities that were on the side of right. The world was arrayed against God’s justice and His laws, and Noah was regarded as a fanatic. PP. 97

“But as the days of Noah were, so shall also the coming of the Son of man be.” Matthew 24:37.

Source References

U.S. scientists fix disease genes in human embryos for 1st time